I am standing in the chambers of the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors. There are many other advocates for justice who came to speak in favor of a moratorium on juvenile fees. I remind the Supervisors first, that Black Women Vote and Black Votes Count.

I am standing in the chambers of the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors. There are many other advocates for justice who came to speak in favor of a moratorium on juvenile fees. I remind the Supervisors first, that Black Women Vote and Black Votes Count.

I represent BWOPA, Black Women Organized for Political Action, Richmond-Contra Costa Chapter. Why is that so important? Because these types of fees have devastated Black and Brown families for decades and no one said anything. And too often, when we have a conversation about institutional racism, there is no Black voice at the table.

What Are These Fees?

In California, juvenile administrative fees are imposed on families whenever a child comes into contact with a County’s juvenile justice system. In Contra Costa County, the fees include cost of care when a child is placed in any detention facility and electronic monitoring fees when a child is released but still under probation supervision. The law allows counties to charge parents for public defender services as well as the cost of drug and substance abuse testing.

The fees are first determined by the probation department. The parent then receives a letter telling her that she owes money as a result of her child’s arrest and incarceration. The probation officer is supposed to tell the parent that she has a right to a statement of the fees, and there is a time limit to contest the fees. The officer is also supposed to tell her that she has a right to a hearing in the juvenile court, and warn her that if she fails to appear, the probation officer will recommend that the court order her to pay the entire amount. (California Welfare & Institutions Code Section 903.45)

Creating Racially-Based Economic Disparity

The imposition of these fees on low-income families clearly undermines the family’s integrity. It also reinforces the economic disparities so prevalent in our society. If the parent does not pay the costs, eventually the debt goes into collections and may become a judgment against her. In Contra Costa County, the probation department has records of almost $17 million of uncollected juvenile fees. The uncollected fees go back as far as 1990. Probation admitted that its practices and policies for the collection of these fees (both the ones previously collected and the $17 million uncollected fees) might not exactly comply with State law.

In a recent bankruptcy case, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals wrote ‘burdening a minor’s mother with debts to be paid following his detention . . . hardly serves the future welfare of the child and hardly enhances the Probation Department’s attempt to transform him into a productive member of society.” (In re Maria G. Rivera.) In that case, the son was incarcerated for 593 days. The family got hit with a bill of almost $20,000.00. The mother paid ½ of it. When she filed bankruptcy after several years, Orange County opposed her discharge in bankruptcy of the remainder of the fees. The Ninth Circuit questioned the County’s actions, stating “the County raises yet another obstacle to Rivera’s efforts to provide her son with the support about which the County claims to be so deeply concerned.”

“Not only does such a [juvenile fee] policy unfairly conscript the poorest members of society to bear the costs of public institutions, operating “as a regressive tax,” but it takes advantage of people when they are at their most vulnerable.” In re Maria G. Rivera, No. 14-60044 (9th Cir. 8/10/16).

“The New Jim Crow” in Contra Costa County

Researchers have documented that in Contra Costa County, a Black child is 8.4 times more likely than a white child to be arrested. That same child is 10.7 times more likely than a white child to be referred to the juvenile court, 10 times more likely to be found delinquent, 15.7 times more likely to be detained before a hearing, and 23.3 times more likely to be incarcerated. (CA Dept. of Justice, published online at www.data.burnsinstitute.org).

Pervasive racial disparity in the juvenile justice system creates massive racially-based economic disparity for families caught up in the system. Black and brown families are devastated by racial disparities in the criminal justice system overall. The realities of “the new jim crow” are particularly heart-breaking when it comes to our children. Research concludes that legal indebtedness contributes to poverty “in three ways: by reducing family income; by limiting access to opportunities such as housing, credit, transportation, and employment; and by increasing the likelihood of ongoing criminal justice involvement.” (Harris A., Evans H., & Beckett, K. (2010). Drawing Blood from Stones: Legal Debt and Social Inequality in the Contemporary United States, American Journal of Sociology, 115, p. 1756.)

A Step Forward

On September 25, 2016, the Contra Costa Board of Supervisors took an important first step. The Court adopted a full moratorium on juvenile fees. The Board suspended the assessment and collection of all fees. Contra Costa joined two other Bay Area counties that have taken similar action. Alameda County repealed the policy. Santa Clara County adopted a moratorium. This is a victory for all children and families. The policy hit Black, Brown and low-income families the hardest.

Advocates to Be Grateful For!

This victory is a direct result of advocacy by the Contra Costa County Racial Justice Coalition, the University of California Berkeley Law Policy Advocacy Clinic and the Reentry Solutions Group. Our community owes a tremendous debt of gratitude for the advocacy of everyone who participated in this effort, including Supervisor John Gioia.

Every election, Margarita Lacabe, my friend and colleague on the Alameda County Democratic Party Central Committee (acdems.org) publishes a Voter Guide. Her goal is to identify the most progressive candidates running for office in Alameda County. Marga does a fabulous job researching credentials, evaluating questionnaires and answers on important issues, and interviewing the candidates whenever possible. This election, Marga has produced two extensive Voter Guides. One Voter Guide talks about the candidates throughout the Bay (not just San Leandro). The other Voter Guide looks at our many state propositions. This week, I am honored to feature Marga as my first guest blogger. Check out Marga’s

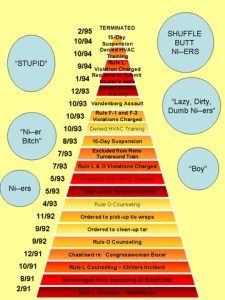

Every election, Margarita Lacabe, my friend and colleague on the Alameda County Democratic Party Central Committee (acdems.org) publishes a Voter Guide. Her goal is to identify the most progressive candidates running for office in Alameda County. Marga does a fabulous job researching credentials, evaluating questionnaires and answers on important issues, and interviewing the candidates whenever possible. This election, Marga has produced two extensive Voter Guides. One Voter Guide talks about the candidates throughout the Bay (not just San Leandro). The other Voter Guide looks at our many state propositions. This week, I am honored to feature Marga as my first guest blogger. Check out Marga’s  We presented evidence of the most despicable racism in any workplace. The jury found that Amtrak’s management was “grossly unprofessional” and engaged in “questionable ethical conduct.” The jury also found that the response from Amtrak’s EEO Office was “woefully remiss.” But, the jury still ruled in favor of Amtrak.

We presented evidence of the most despicable racism in any workplace. The jury found that Amtrak’s management was “grossly unprofessional” and engaged in “questionable ethical conduct.” The jury also found that the response from Amtrak’s EEO Office was “woefully remiss.” But, the jury still ruled in favor of Amtrak. And so that was decided. Abner Morgan, to his credit, co-signed Howard’s statement by saying that I was his lawyer and he was not going to let anyone else argue his case. I got it. So I gathered my wits, my spirit, took charge of the situation and got us all to Washington, D.C.

And so that was decided. Abner Morgan, to his credit, co-signed Howard’s statement by saying that I was his lawyer and he was not going to let anyone else argue his case. I got it. So I gathered my wits, my spirit, took charge of the situation and got us all to Washington, D.C.

This time, the jury got it right and awarded Abner $500,000.

This time, the jury got it right and awarded Abner $500,000. Ricardo Perez is charged with felony oral copulation with my client, Jasmine. It is apparently well known that he was “one of her regulars.” Since she was still a minor, he was actively engaged in the commercial sexual exploitation of a child

Ricardo Perez is charged with felony oral copulation with my client, Jasmine. It is apparently well known that he was “one of her regulars.” Since she was still a minor, he was actively engaged in the commercial sexual exploitation of a child