Black August began in the 1970s to mark the death of imprisoned Black Panther, prison activist and author, George Jackson. George Jackson died in a prison rebellion at San Quentin State Prison on August 21, 1971. His memorial service was held at St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland on August 28, 1971. His death sparked demonstrations here and around the country to protest the conditions under which he lived and died. In Attica, New York, prisoners launched a silent fast to commemorate Jackson’s life and mourn his death. Three weeks later, they staged what would become the most significant prison rebellion in American history.

Black August is a time to honor freedom fighters, and martyrs of the Black freedom struggle. It’s a moment of respect for those whose lives were lost in the struggle. A moment to appreciate those who are still dedicated to ending mass incarceration, racism and double standards in the criminal justice system.

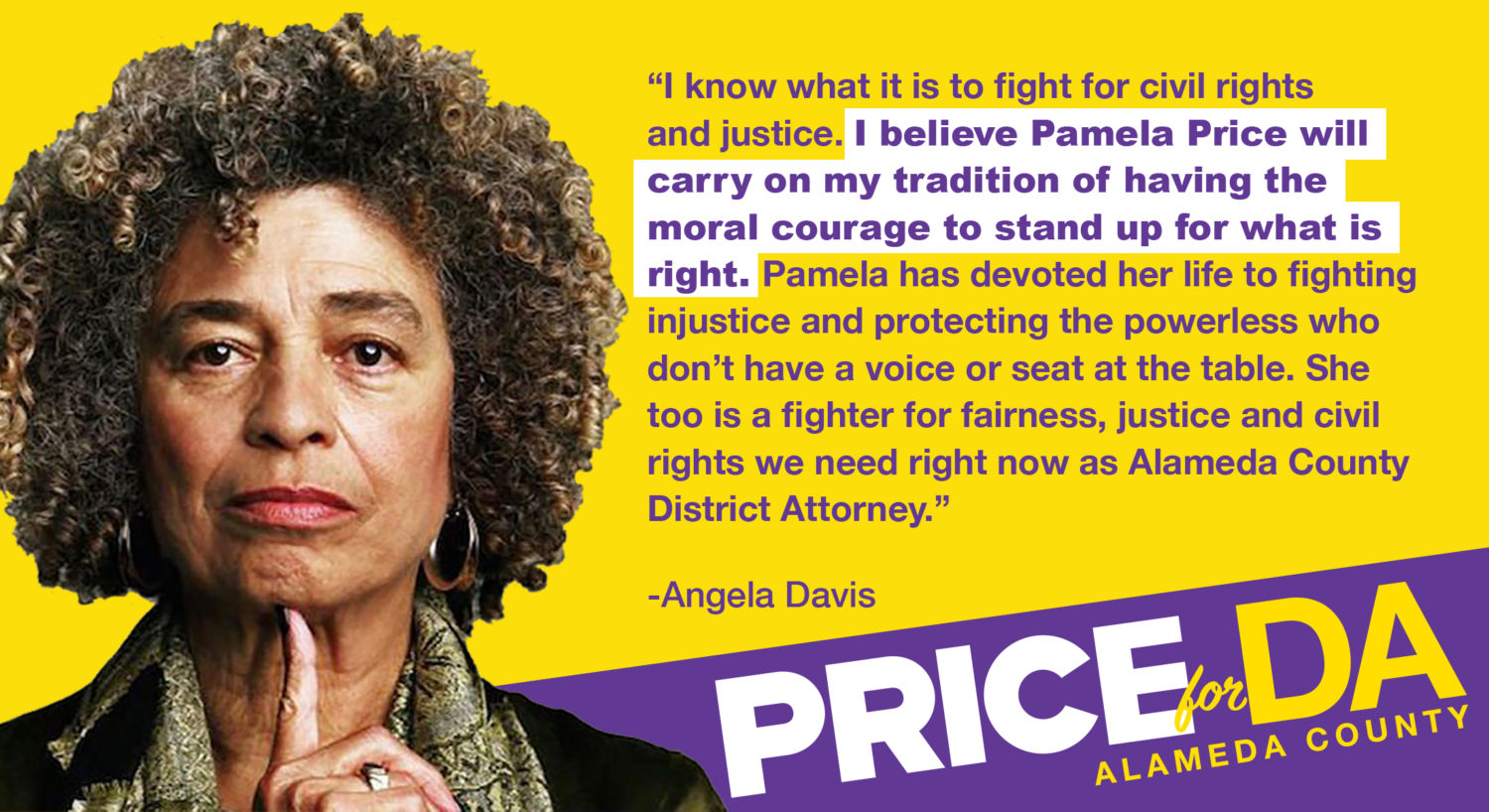

Angela Davis is an international symbol of the fighting spirit of Black August. While organizing on behalf of George Jackson and two other prisoners accused of murder, Davis herself wound up behind bars. In 1971, Angela was charged with criminal conspiracy, kidnapping and first-degree murder. A massive international movement formed to free her and she was cleared of all charges. The experience solidified her already deep determination to fight for fundamental change in America.

The Lessons of George Jackson

George Jackson was only 29 years old when he died. He was serving a “1 year to life” sentence. He was 18 in 1961 when he was arrested for participating in an armed robbery. Another 18-year old used a gun to steal $71.00. George admitted that he was in the car. Both young men pled guilty to the crime. Apparently, because George had a lengthy juvenile record, his life was considered “expendable.” He was only 19 when he was convicted and sent to San Quentin State Prison.

In the 9 years before his death, George Jackson co-founded a Black Panther Party chapter and the Black Guerilla Family at San Quentin. George became a committed activist who resisted racism and physical assaults inside prison walls. His eloquent prison writings were published and became immensely popular with an international audience concerned with the conditions of incarceration in American prisons and the unequal and harsh prosecution of Black, Brown and indigenous people. Prior to his death, he spent years in solitary confinement. By accounts from those who knew him, George Jackson was charismatic, intelligent, strong and soft-spoken.

In 1970, barely a year before his death, he was accused of killing a correctional officer at Soledad State Prison. The State never completed the case against him. He was killed a few days before the trial started.

The tragedy of George Jackson’s young life and death speaks loudly to our current movement for criminal justice reform. The idea that an 18-year-old should be incarcerated for “1 year to life” for being an accessory to a crime seems barbaric today. That he should die in prison less than 10 years later sounds like a tragedy that should have somehow been avoided. But it was, and continues to be the reality for too many Black, Brown and poor young people whose lives are considered “expendable.” Fifty years after the death of George Jackson, we are still fighting deeply embedded racial injustices and economic disparities in our criminal justice system.

A Scientific Basis for Change

In his book, “Just Mercy,” Bryan Stevenson says that “none of us want to be judged by the worst thing we’ve ever done in our lives.” But, that is exactly what happened to George Jackson. Today, the neuroscience tells us that “adolescents often lack the ability to make mature judgments, control their impulses and consider the consequences of their actions.” In 2005, in Roper v. Simmons (2005), 543 U.S. 551, the U.S. Supreme Court accepted the research of the American Psychological Association (APA) and rejected the death penalty for a 17-year-old. The APA also presented its early MRI research on brain function indicating that the brain continues to develop through young adulthood in areas that may bear on adolescent decision-making.

Point No. 4 of our 10-point platform incorporates the scientific research that was accepted by the United States Supreme Court, more than 15 years ago. We will not charge juveniles as adults. Nor should we expect a magical transformation in their decision-making the day that they turn 18. There is a transitional period that for some may be completed by age 25. For others, it may continue well past age 25.

When I am elected to serve as District Attorney of Alameda County, I commit to (1) stop over-criminalizing our youth; (2) stop charging and/or incarcerating youths under the age of 18 as adults; and (3) establish age-appropriate programs to prevent and address criminal violations by young people between the ages of 18 and 25.

Postscript

The incarceration, life and death of George Jackson shows that incarceration, as practiced in America over the last 60 years, does not work. It does not create positive outcomes in the lives of the person incarcerated, their victims, their families or their community. It does not make us safe. We must develop and embrace alternatives to incarceration that repair the harm, the person and the beloved community. All of us, and especially our children, deserve nothing less than our best efforts.